The path that leads us to the fifth circle allows us to get beyond the remaining tensions, to celebrate the communion of mastery and freedom. First, we have to free ourselves from paradoxes, and even contradictions by freeing ourselves from what determines us physically so as to attain the essence of what frees us spiritually. Each stage in this quest for the self requires mastery, discipline, choices and ethics. Each of these stages reproduces the same questions with more and more intensity: Why am I what I am? Why do I think what I think? True freedom can only be a liberation:

freedom is an ideal in a process, an ever-renewed experience, it is never achieved. It is interesting to note the similarity between this mystical observation and Freud’s theory of psychic determinism: we are bound, consciously and/or unconsciously, and we always have to go back to the source, to our blocks and repressions, if we are to overcome the tensions of the neuroses that inhabit us. We can never escape them, and we must never be deceived by even the most beautiful manifestations of sublimation (usually through art): sublimation is not freedom, but merely a way of expressing and managing our imprisonment and/or traumas.

Many philosophical theories share this sense of impotence, or this necessary awareness of the determination in the natural order, in societies and in the individual.

Spinoza’s determinism or Marx’s historical materialism do not entail fatalism or an inevitable passivity; on the contrary, they essentially point to the nature and limits – and therefore the actual powers – of human action. It is not a matter of measuring power by the standards of the will, but of inverting the terms of the question: what can I want? The answer given by the existentialist Sartre is radical in two senses. Because

‘existence precedes essence’, I am condemned to be free and must assume the totality of both my will and my power. I am therefore fundamentally free, and absolutely responsible: attenuating circumstances exist only for minds in bad faith that try to hide behind ‘circumstances’ . . . or faith. In the name of that freedom, it is also natural and logical for the intellect to produce an ethics that is rational, autonomous, secular, individual and demanding, because it must never neglect the human community in which and for which it finds expression. We are a long way – a very long way – from the paths of mysticism, faith and the extinction of the ego; here, the subject knows that he is alone, says ‘I’ and assumes his freedom as an individual. As the Lithuanianborn French philosopher puts it, freedom is ’the ability to do what no one else can do in my place’. And yet, as we go down the road to freedom, we find the same hopes, the same demands, the same need for ethics, or even laws, to regulate and give substance to freedom itself. Freedom demands awareness, rigour and, paradoxically, discipline on the part of the subject, the ego/self, the believer and the philosopher as well as the mystic. No matter whether we are alone or part of a community, we enter the virtuous circle of the experience of freedom and liberation, and we never emerge from it to the extent that we are human. For whilst freedom is a precondition for responsibility, one of the dimensions of responsibility is that we are completely responsible for the use we make of our freedom. Whilst the law can regulate, it cannot codify everything: in human relationships, friendship, love or a mere encounter, two free beings must recognize their mutual sensibilities and aspirations. The law sometimes allows us to say things that humanity, or common decency, invites us not to express. The quest for a reasonable freedom consists as much in demanding legitimate powers as in learning to master them.

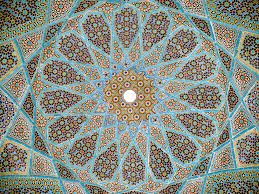

We are at last coming to the end, or perhaps it is the origin. Art is the privileged school for this encounter between mastery, freedom and liberation. A pianist or violinist who plays Mozart, Schubert or Beethoven spends years trying to master a difficult technique. The rules are constrictive. He or she must begin again and again to practise, to internalize a technique . . . concentrate, master the emotions, the body, the fingers. The technique is gradually acquired. The rules are assimilated, and they give the man or woman who has mastered them an unexpected freedom. His or her hands fly and infinite realms of possibility, expression and improvisation open because the laws, rules and techniques of the genre have been so completely mastered that they appear to be natural, simple and easy. Mozart or Beethoven suddenly seem to be, to be there and to create being. In art, a technique that has been mastered is a liberation. When Baudelaire speaks of the ‘evocative magic’ of modern art, he expresses the same idea (and introduces the possibility of transgression): a complete mastery of the piano, the paintbrush or language grants access to a freedom that is made possible through the exercise of constraint itself. After having studied painstakingly, the musician, painter or poet suddenly plays, and his expressive and evocative powers appear to both limitless and almost magical. The mastery of a technique and its external rules allow us to concentrate on the inner universe, with its emotional density and shades of intensity: we can set a feelings, or words, or colours to music . . . and even, through an alchemy of poetic correspondence, colour the sound of words, or put words to colour tones: The variations of this theme are endless. This expressive capacity is indeed freedom and a liberation: everything becomes possible. Religious and mystical experience has a lot in common with this kind of artistic asceticism: study, self-control, mastery of the ritual, the rules and of apparent forms is the path that leads us inside the self in order to encounter and transcend the self, and to experience the spiritual liberation of being. Just as there can be no free artistic improvisation without a mastery of technique, there can be no liberating spiritual experience without study, or without a codified and integrated ritual. This is, however, not without its dangers, as we must never lose sight of our goals: an artist who concentrates solely on technique destroys art, and the believer or mystic who becomes obsessed with ritual destroys both meaning and spirituality. Basically, the same is true of our public life and interpersonal relationships: the law and the rules certainly help to protect our respective freedoms, but too many laws eventually stifle and confine us. That is the price we pay for our freedom: we must experience paradoxes, reconcile opposites, establish balances and harmonies and never lose sight of either apparent illusions or profound ends.

I disagree lol

I agree.