The outward expression of Muslim identity is the articulation and demonstration of the faith through consistent behavior. Faith, understanding, education, and transmission together constitute the substrata of Islamic ethics and should therefore guide the actions of the believer. To be Muslim is to act according to the teachings of Islam, no matter what the surrounding environment, and there is nothing in Islam that commands a Muslim to withdraw from society in order to be closer to God. It is actually quite the opposite, and, in the Qur’an, believing is often, and almost essentially, linked with behaving well and doing good. The Prophet never stopped drawing attention to this dimension of Muslim identity, and its authentic flowering entails the possibilities one has of acting according to what one is and according to what on believes.

This “acting,” in whatever country or environment, is based on four important aspects of human life: developing and protecting spiritual life in society, disseminating religious as well as secular education, acting for justice in every sphere of social, economic, and political life, and, finally, promoting solidarity with all groups of needy people who are forgotten or culpably neglected or marginalized. In the North as well as in the South, in the West as well as in the East, a Muslim is a Muslim when he or she understands this fundamental dimension of his or her presence on earth: to be with God is to be with human beings, not only with Muslims but, as the Prophet said, “with people,” that is, the whole of humankind: “The best among you is the one who behaves best toward people.”

For the individual, to bear the faith has to be translated into action that is consistent with it. One may act as oneself for oneself before God. But this is clearly not enough, and one is bound to move in the direction of participation, which clearly expresses the idea of action with an other, in a given society, with the fellow-citizens of whom it is composed. The fourth pivot of Muslim identity brings together these two dimensions of acting and participating, or, in other words, the individual and the social being, which define being Muslim in relation to society and the world.

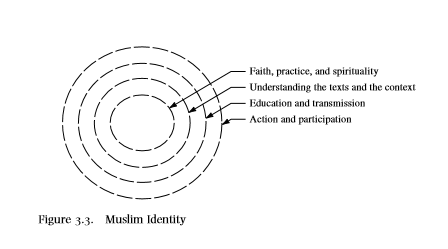

These four elements give an adequate picture of the fundamentals of Muslim identity, individual and social, separate from its cultural reading in a specific region of the world. The kernel of faith, with practice and spirituality, is the light by which life and the world are perceived. Understanding the Texts and the context allows one to order one’s mind both in relation to oneself and in relation to the environment. In a broader circle, education and transmission make it possible both to hand on the pledge as a gift and to pass on the message. And, finally, in an even broader context, actionand participation are the full demonstration of this identity through the way one behaves for oneself, toward the other, and toward Creation (action) and with one’s fellow-citizens and the whole of humankind (participation). It becomes apparent, then, that the definition of Muslim identity can be only of something open and dynamic, founded, of course, on basic principles but in constant interaction with the environment. The diagram in figure 3.3, beginning with faith at the core and moving on to expression through engagement with people, participation, demonstrates fairly clearly the way we have articulated the definition of Muslim identity.

The great responsibility of Muslims in the West is to dress these four dimensions of their identity in a Western culture while staying faithful to the Islamic sources, which, with their conception of life, death, and Creation, remain the fundamental frame of reference. Keeping in mind both the distinction between the usul (the fundamental elements of the religion) and the furu (the secondary elements), the three levels of maslaha—that is, al-daruriyyat (the indispensable), al-hajiyyat (the necessary, the complementary), and al-tahsiniyyat (the additional enhancing, the perfecting)— as well as the areas in which ijtihad may be applied, Muslims, both ulama and group leaders, should provide Western Muslims with appropriate teachings and regulations that will make it possible for them to protect and to actualize their Muslim identity, not as Arabs, Pakistanis, or Indians but as Westerners. This slow process has actually been taking place for only about twenty years, and it is proceeding, making possible the birth of a new and authentic Muslim identity, neither completely dissolved in the Western environment nor reacting against it but rather resting on its own foundations according to its own Islamic sources. In the second part of this book I shall try to give concrete illustrations of these dynamics and the direction in which I believe they should move together.

At a middle point between being Muslims without Islam and being Muslims in the West but outside the West, there is the reality of Muslims aware of the four dimensions of their identity and ready, while acknowledging the demands it will make, to be involved in their society and to play their part as Muslims and as citizens. There is no contradiction between these two allegiances as long as Muslims carry out their commitment to be active in conformity with the law and that they are not required to shed any part of their identity. This means that their faith, their perception of life, and their spirituality, which they need in order to learn and understand, to speak and educate, to act for justice and solidarity, should be respected by the country in which they are either residents or citizens.

Neither should there be any legal or administrative discrimination against the freedom of Muslims to organize themselves and to respond adequately and effectively to the demands of their faith and their conscience. These obstacles are met with daily in Western countries both because of the image of Islam that is disseminated by some of the mass media and as a result of the widespread feeling that there is an “Islamic threat,” which is reinforced by news of dramatic events in Algeria, Afghanistan, and in the United States in September 2001. Many Westerners—politicians and intellectuals, as well as ordinary people—who are used to living in a secularized society tend to believe that the only Muslims they can trust are those who do not practice their religion and reveal nothing of their Muslim identity. Out of fear, or sometimes out of ill intent, they interpret the law of their country tendentiously and discriminatorily and sometimes have no hesitation in justifying their behavior by recourse to the argument that they must resist the “fundamentalists” and “Muslim fanatics.”

Such attitudes are in evidence if we look at numerous rights denied to Muslims (e.g., construction of mosques, general organization of activities, allocation of grants, or simply freedom at a social level), while other religions and institutions, under the same law justly applied, have enjoyed these rights for decades.

It is nonetheless the law that should be the criterion and reference point, and a careful study shows that in most Western countries the constitution allows Muslims to live largely in accordance with their identity in the sense by which we have defined it. Muslim leaders and intellectuals should on the one hand demand and require the just and equitable application of the law with respect to all citizens and all religions. And on the other, they should face up to their responsibilities by using the broad freedom they enjoy in the West and trying to provide Muslim communities, through courses, study circles, and all kinds of institutions and organizations whose essential aims are to keep Islamic faith and spirituality alive, to spread a better understanding both of Islam and of the environment, to educate and pass on the message of Islam, and, finally, to see to it that Muslims get really involved in the society in which they live. There is nothing to stop them from doing so and although many initiatives have been taken in this direction over the past several years, the teaching given has often remained traditional. We shall return later to these forms of Islamic education, which have been provided without much thought to the context in which Muslims live.

This proposal means, above all, that we must develop, as we have said, a new and more confident attitude, based on a clear awareness of the essential features of our “being Western.” This understanding should lead Muslims to evaluate their environment objectively and fairly. While respecting the requirements of their religion, they must not neglect the important potential for adaptation that is the distinctive characteristic of Islam. This is what has allowed Muslims to establish themselves in the Middle East and in Africa and Asia and, in the name of one and the same Islam, to give their identity concrete reality in specific and diverse shapes and forms. Again, Islam as a point of reference, is one, but its realization assumes recognition of the history and the social and cultural context in which it exists. In this sense, as we have said, there should be an Islam that is rooted in the Western cultural universe, just as there is an Islam rooted in the African or Asian tradition. Islam, with its Islamic sources, is one and unique; the methodologies for its legal application are several, and its concretization in a given time and place is by nature plural. From the Islamic point of view, adapting, for the new generations, does not mean making concessions on the essentials but, rather, building, working out, seeking to remain faithful while allowing for evolution. With this aim, Muslims should take advantage of the most effective methods (e.g., of teaching, management) and scientific and technological discoveries (which are not in themselves in conflict with Islam, as we have seen) in order to face their environment appropriately equipped. These developments belong to the human heritage and are part of Western society, and Muslims, especially those who live in the West, cannot ignore them or simply reject them because they are not “Islamic.”

On the contrary, the teaching of Islam is very explicit and comes into its own here: in the area of social affairs (al-mamalat) all the ways and means—the traditions, arts, clothes—that do not, either in themselves or in the use to which they are put, conflict with Islamic precepts become not only acceptable but Islamic by definition. Consequently, Muslims should move toward exercising a choice from within the Western context in order to make their own what is in harmony with their identity and at the same time to develop and fashion the image of their Western identity for the present and the future.

I enjoyed reading this article! Thank you Mr. Tariq Ramadan.