If we listen to men and women living in the societies of the South, from Latin America to India and Indonesia or the African continent or the Middle East, we find that globalization is perceived mainly as a form of Westernization. If we listen to African-Americans, Latinos and new citizens of the United States, or the citizens of Canada, Europe or Australia, we find that they are uneasy about their culture, values and memories. Relations of power do exist, and debates about universals and specific identities obviously reflect the tensions between tradition and modernity, but they are really debates about ‘self’ and ‘other’. They are about defining ourselves, giving our history a dignity, our memory a legitimacy and our tradition (defined as cultural and/or religious) a meaning. They are about our presence and our hopes.

Officially, pluralist societies must take into account the diversity of the culture and historical experience of their citizens and residents. Values, symbols and language shape our consciousness, psychology and worldview, and so too does the memory of colonization, migration, exile and settlement (and sometime of rejection and racism). Rather than allowing our memories to be torn apart by squabbles over universals or the higher truths of rival points of view, contemporary societies, both rich and poor and in both the North and the South, should be doing more to institutionalize the teaching of a common history of memories. They should be combining the wealth of all our memories, explaining different points of view, and trying to understand collective consciousnesses and collective hopes as well as historical wounds and traumas. We have already said that, as a matter of urgency, modern man must reconcile himself with a sense of history, and rediscover the essence of the cultural and religious traditions in an age of globalization. It cannot be said too often that globalization itself is producing a culture that exists on a world scale. That culture has a tendency to make other traditions and cultures, with their symbols, rites, arts and food, look ‘exotic’ or peripheral, though some of their artistic and culinary products can of course be integrated into the logic of its economy because they hold out the promise of substantial profits.

From India to Africa, a new consciousness is awakening in quest for spirituality and meaning. The same is true of Western societies: it is therefore important to produce a better understanding of these different traditions in order to ensure that they do not become fantasy ‘refuges’ from materialism and/or the consumer society. There is a certain enthusiasm, sometime joyous and sometimes naive, for Buddhism and Jewish, Christian and Muslim mysticism, but it tends adulterate the very essence of the teachings of these traditions. ‘Reincarnation’ has come to mean a reassuring story about ‘coming back’, whereas it actually refers to the fact that we are bound by cycles of suffering. Sufism has been turned into ethereal flights of fancy that make no ritual demands, whereas the Sufi tradition itself has always been very demanding in terms of its practices and disciplines towards the initiate than towards the ordinary faithful

Languages, cultures and traditions should also be explained and promoted in our schools, just as they should be celebrated and encouraged by local cultural policies. Given the dominance of English, fast food and stereotypical consumerism, it is important to teach children more than one language, to introduce them to new intellectual worlds with different terminological points of reference, and thus to multiple sensibilities, tastes and points of view. Languages convey and transmit sensibilities; they have and are particular sensibilities. Studying the meaning of symbols, practices and customs calls into question the legitimacy of our own symbols, practices and customs and relativizes our certainties and pretensions. Drinking tea in China is a ceremonial affair that reveals a way of life, a conception of time, conviviality and dialogue. That ceremony now has to compete with – or resist – the standardized consumerism offered by the big multinationals, which are now introducing, and gradually imposing, a different view of life.

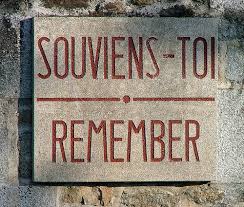

We live in an era in which it seems imperative to come to terms with the multiplicity of our memories, and to defend the equal right to be, to express ourselves and to speak out. Memories introduce us to different views of history, language and the many traditions we have to understand for what they are. When modernity laid claim to a truth, it was the truth of autonomy, of the freedom that is its precondition, and of the diversity that results from it. The ideologues of modernity have (with modernism) turned it into a particular and exclusive tradition that has to prevail because it is superior. It therefore comes as no surprise to see some women and men in both the South and the North resisting a dangerous standardization. They eat ‘slow food’ whereas the majority eat ‘fast food’, and prefer healthy produce, fair trade and local produce, and food and drink that is environmentally friendly. They are beginning to resist and are keeping a watchful eye on the surprises that might go with the economic – and perhaps cultural – rise of China and India at a time when the United States appears to have been so weakened and when Europe seems to have lost all sense of direction. They are, then, beginning to resist and in that sense they are profoundly modern. The paradox is that they are now demanding, in and through their cultural and religious traditions, precisely what the humanists, who were the precursors of modernity, were demanding when they rebelled against tradition, namely autonomy, freedom and diversity. This is a disturbing reversal . . . unless it is precisely the same process and involves precisely the same relations or force. Perhaps we have to admit that modernity is basically nothing more than one tradition amongst others. Depending on the historical circumstances and the endogenous and exogenous relations of domination and power, ‘modernity’ does not necessarily do more than any other tradition to guarantee us autonomy, freedom and diversity. Tradition or modernity? This is a terminological illusion or a tautology: despite all the differences and the gains that have been made, both modernity and tradition are indirect expressions of power relations. ‘One must be absolutely modern!’ cried Rimbaud because he felt, deep down, that there was no way – modern or otherwise – of escaping his tradition.