Many works have been written on this subject, and many Muslim intellectuals since the beginning of the twentieth century have expounded the broad outlines of Islamic economics. We shall limit ourselves here to indicating by way of summary three principles that explain economic activity without bringing in overwhelming amounts of legal detail.

Tawhid and Vicegerency. We have referred in part I to the relationship that exists between the owner—God—and the vicegerent—the human being— in Islam. There is absolutely no doubt that in the realm of economics, this relationship has a profound impact. The teaching of tawhid is fundamental: God alone has ownership in the absolute sense, and He has put the earth at the disposal of humankind. “What is in heaven and on earth belongs to God.” “Are you not aware that God has made subservient to you all that is in the heavens and all that is on earth, an has lavished upon you His blessing, both outward and inward?” The idea of vicegerency (khilafa) gives duties priority over rights. Everyone may, and has the inalienable right to, enjoy all natural resources, since they are put at our disposal by the Creator; but this enjoyment cannot extend to disturbing the natural order by savage exploitation of the elements and disrespect for the “signs.” Ecological considerations are inherent in the Islamic philosophy of action: to enjoy resources before God, requires that we respect them. There is of course the original permission, but there are limits torespect. Thus, all the elements are signs (ayat) in creation, sacred in themselves; this point alone has important consequences.

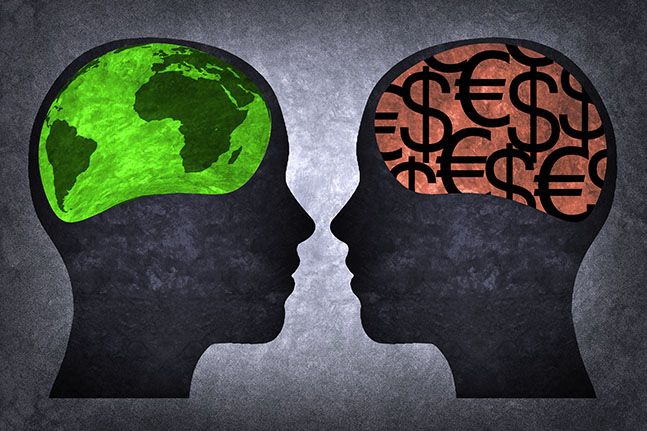

The Creator desires the good of humankind, and we should not forget that desire. What is true on the ecological plane, with regard to use of resources, is also true in the sphere of production. We have already said that what makes a good product is its moral quality: the parameters of productivity, profitability, costing, and so on are nothing in themselves and are void of meaning if they are used to measure the production of what is useless, worthless, or, more broadly, destructive. Clearly, humankind must produce, but never simply for profit; humankind must indeed consume, but always commensurately with its real needs. We must not forget the need to take into account the higher interest of society, which, echoing the divine values, limits all egoistical and thoughtless exploitation. This is the problematic contained in the recognition of private property.

Private Property. Ownership and enjoyment of material possession is permitted in Islam and has its place in the framework that we have referred to many times: the use of goods must respect revealed moral guidance and, further, must take into account the interest of the society as a whole. In this philosophy of the existence and management of possessions, the right and freedom of people to enjoy goods and to acquire property are considerable. The principle for acquisition is found in the Qur’an: “One part of what men acquire through their work is their own; one part of what women acquire through their work is their own.”18 The first teaching to be deduced from this verse is the recognition of property acquired through work. This is what the majority of Muslim jurists point to. We have already referred to the fundamental right to work, and the possibility of acquiring goods is a logical consequence: it may be the salaried work of employees, agriculture, commerce, fishing, hunting, or other work. The only condition, the fundamental condition, is that the work be within the bounds of what is considered legal (which means for Muslims the avoidance of dealing in forbidden merchandise, gambling in all its forms, monopolies, usury, and speculation). There are other means of acquiring property: inheritance, capital, zakat (for the poor), awqaf (endowments), and gifts, and we find in the standard works of law and Islamic jurisprudence commentaries and detailed analyses of each of these means.

The recognition of property assumes the social organization to protect it. This protection is fundamental in Islamic law: in the classification proposed by the scholars, which we have already mentioned with reference to al-Shatibi, it forms part of the daruriyyat (essential needs) alongside the protection of religion, of the person, of intellect, and of family ties. So property is inalienable. But it must be stated that its management is subject to conditions whose absence calls for the intervention of the public authorities. Without going into detail, here are three situations that would require intervention on the basis of the principles expounded: (1) management involving corruption, theft, unjust exploitation of employees, trade in illegal products, financial fraud; (2) management that goes against the common interest, which might mean anything from the creation of a monopoly to irresponsible squandering; (3) a case of force majeure: natural disaster, wars, or higher demands of the community. Clearly, all these exceptions have to be codified and must adhere to the rules of due process of law to which every citizen is entitled. Even if all these means of intervention do not exist in the West, it is good to remember what situations are defined as abusive or exceptional.

The general principle is expressed by a sort of contract between society and its property-owning members. In exchange for protection, and well in advance of any intervention, which should be the exception rather than the rule, property owners have a duty to society to manage their belongings in a moral way. The basis of their social and economic freedom is not put at risk, but each of them is required to respect the community as a whole. Similarly, society will encourage economic activity, and people’s efforts to multiply their goods will contribute to the success of the social strategy. The state, as happens almost everywhere, must guarantee respect for the areas of maneuver that are essential for economic activity and investments. The limitations are necessary for ethical reasons, because people always lose the sense of moderation and well-doing when there is too great a temptation to profit. It is unjust not to trust in people’s good qualities, but it is madness to turn a blind eye to their weaknesses.

Requiring people of faith to take care to retain the moral quality in the management of their affairs and to observe the principles of law and Islamic jurisprudence concerning property has two more aspects whose nature is to ward off excess. The first is the obligation to pay zakat, to which we have already referred. This purifying social tax is a tax on property and not only on income. Muslims have to give a percentage of their goods to an institution, an organization, or directly to the poor, usually on the basis of a reckoning of their material situation over the period of a year. We have mentioned the religious importance of this payment and its profoundly moral implication. It also has explicit significance for social justice and solidarity between the rich and the poor. It must be added, however, that zakat is in itself an invitation to put one’s possessions to work and to profit from them without the hoarding that would otherwise be possible. The second limitation concerning management of property is one of the most rigorous Islamic prohibitions in the area of social affairs. We often simply say and recall that Islam is against usury, or against interest, without going into the consequences of this statement. However, it is essential to analyze it so that we may look at concrete solutions that could be

brought to bear in response to the failing current economic system. The prohibition of riba (which we shall define later) is contained in the economic philosophy that underlies it, whose broad outlines we have traced here; it implicitly demands that we consider an alternative economic system. It cannot remain simply theoretical, and we shall see later that it requires very determined local commitment.

The Prohibition of Riba. There are several definitions of the term riba, depending on whether the intention is to restrict or extend the scope of its prohibition in the realm of economic activity. The Arabic word riba is derived from the verb raba, which means to “increase” or “augment.” There are various legal opinions on the nature of the prohibition itself, but the ulama of the past and of today are almost unanimous in understanding that it formally prohibits any rate of interest and any form of usury, because the idea that underlies the notion of riba is one of profit that is not in exchange for any service rendered or work performed: it is a growth of capital through and upon capital itself. It is also considered that a form of riba exists in situations of unequal exchange: “this is usury on exchanges” or “on unequal exchanges,” which relies on the famous hadith of the Prophet: “Wheat for wheat in equal parts and from hand to hand; any surplus is usury. Barley for barley in equal parts and from hand to hand; any surplus is usury. Dates for dates in equal parts and from hand to hand; any surplus is usury. Salt for salt in equal parts and from hand to hand; any surplus is usury. Silver for silver in equal parts and from hand to hand; any surplus is usury. Gold for gold in equal parts and from hand to hand; any surplus is usury.” The idea that emerges from this hadith is one of equality and simultaneity in exchange, with the intention that the terms of exchange should be very clear to both parties. Many hadith introduce precise details that insist on the importance of the conditions of exchange, and jurists of all the Sunni schools have deduced from them a formal prohibition against speculation, although there is some diversity of interpretation regarding certain types of economic and financial procedures. The conclusion drawn by Hamid Algabid, former prime minister of the Republic of Niger and former secretary general of the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OCI), is clear and legally precise: “Whether we refer to usury on loans of money or on exchanges, the minuteness of the detail of the prohibitions and obligations in the Sunna shows that hoarding in all its forms is rigorously condemned, and is pursued in all circumstances, no matter how improbable. The clear definition of what is lent and what is restored, what is sold and the price paid for it is an absolute rule—clear definition of the object itself and of the time frame. Speculation is banned as acquisition of wealth without justification; that is to say increasing the value of the object of the exchange without anything legitimate being added to it in return (such as work, treatment, transport, preparation).”

So what emerges on the strictly economic level is a double prohibition contained in the notion of riba when one understands it in the Qur’anic sense of increasing the value of goods without performing any service: (1) the prohibition of interest on capital; (2) the prohibition of interest on exchanges that, being based on speculation, monopoly, or other “unequal conditions,” is not a profit derived from honest trade. These are the general principles of the prohibition, and every epoch must consider the current economic practicalities in order to measure how far they comply with the principles and the ethics. It is in fact clear that the very definition of riba is a function of the type of activities that arise in historical situations and of the extent of the application of the definition. The inclusion of this notion in the ethical order that reminds us of the transcendent and collective dimensions is of prime importance, and there is no doubt that this is the essential point of the prohibition. It is not a question of suffocating human activity—quite the reverse; but it is a question of making it just and equitable, of “separating the good grain from the weeds.” The progression in the order of the Revelations that led to this prohibition is very eloquent. The first verse revealed is a kind of allusion and brings out the moral deficiency implicit in paying interest on personal transactions: “Whatever you may give out in usury so that it might increase through

[other] people’s possessions will bring [you] no increase in the sight of God—whereas all that you give out in charity, seeking God’s countenance, [will be blessed by Him] for it is they, they [who thus seek his countenance] that shall have their recompense multiplied.” This thought is addressed to debtors who are asked, implicitly and from a moral point of view, not to undertake this kind of borrowing. The verses of the second Revelation dealing with usury speak of the example of the Jews, who had broken the prohibition: they are the creditors who are focused on here and, in their practice of usury, they are said to “consume people’s goods unjustly.” The notion of justice takes priority: “We have forbidden the Jews excellent foods which were formerly permitted to them; this is because of their prevarication, because they have often strayed from the way of God, because they have practised usury which had been forbidden to them, because they have consumed people’s goods unjustly.” The third stage is an exclamation addressed to the Muslims and restricted to a specific practice: “O you have attained to faith! Do not gorge yourselves on usury, doubling and redoubling it—but remain conscious of God, so that you may attain to a happy state.” The verses containing the formal prohibition are among the last revealed to the Prophet, and Umar later expressed regret that the Prophet had not been able to make its meaning more precise for his Companions.

Nevertheless, it is explicit, and it makes it clear that it is a matter of distinguishing between good and bad practices in a purely moral sense: trade that can legitimately produce profit is founded on justice if it follows criteria that will prevent it becoming an unequal exchange leading to exploitation of some by others: “Those who gorge themselves on usury behave but as he might behave whom Satan has confounded with his touch; for they say, ‘Buying and selling is but a kind of usury’—the while God has made buying and selling lawful and usury unlawful. Hence, whoever becomes aware of his Sustainer’s admonition, and thereupon desists [from usury], may keep his past gains, and it will be for God to judge him; but as for those who return to it—they are destined for the fire therein to abide! God deprives usurious gains of all blessing, whereas He blesses charitable deeds with manifold increase. And God does not love anyone who is stubbornly ingrate and persists in sinful ways. Verily, those who have attained to faith and do good works, and are constant in prayer, and dispense charity—they shall have their reward with their Sustainer, and no fear need they have, and neither shall they grieve. O you who have attained to faith! Remain conscious of God, and give up all outstanding gains from usury, if you are [truly] believers; for if you do it not, then know that you are at war with God and His Apostle. But if you repent, then you shall be entitled to [the return of] your principal: you will do no wrong, and neither will you be wronged. If, however, [the debtor] is in straitened circumstances, [grant him] a delay until a time of ease; and it would be for your own good—if you but knew it—to remit [the debt entirely] by way of charity. And be conscious of the Day on which you shall be brought back unto God, whereupon every human being shall be repaid in full for what he has earned, and none shall be wronged.”

Usury, which appears to bring in money and increase one’s capital, and almsgiving, or the purifying social tax, which appears to diminish it, stand face to face: in the divine balance, by the measure of conscience and the gauge of human benefit, they are ultimately the opposite of what they seem: usury is a loss and almsgiving is a gain. The purpose of the prohibition is to put people in a relation of transparence, equity, and humanity: “Do not treat anyone unjustly and you will not be unjustly treated.” So it is a matter of refusing all forms of exploitation and of encouraging fair trade. The rich at the time of Muhammad could react only negatively to the meaning of this message directed them, as people have always reacted to prophetic revelations, from Noah to Jesus: “Whenever We sent a prophet to any community, those of its people who had lost themselves entirely in the pursuit of pleasures would declare, ‘Behold, we deny that there is any truth in [what you claim to be] your message.’ In the same way, this message cannot but arouse the disapproval of the richest people today because it is essentially a determined rejection of economic servitude, financial slavery, and all humiliation. There is no scope for distorting its meaning: it charges people to find the most appropriate system for their time, provided that it respects the foundational principle of expressing an economy with a human face, inevitably opposed to interest, speculation, and monopolies.

We are well and truly on the way to opposing the world economic order. It could not be clearer. The rich countries, like the wealthy merchants of Mecca in times past, cannot fail to see a danger in local and national movements whose aim is to remove themselves from the “classical” economic system. Nothing could be more normal. But we now know that the Northern model of development is unexportable: a billion and a half human beings live in comfort because almost four billion do not have the means to survive. The terms of exchange are unequal, exploitation is permanent, speculation is extreme, monopolies are murderous. The prohibition of riba, which is the moral axis around which the economic thought of Islam revolves, calls believers to reject categorically an order that respects only profit and scoffs at the values of justice and humanity. By the same token, the prohibition obliges them to consider and to work out a model that comes closer to respecting the prohibition. In the West, as in the East, we must think of a global alternative, and local projects must be implemented with the idea of leaving the system to the extent possible and not affirming it through blindness, incompetence, or laziness.