This double function of shahada should be more explicitly expressed in the six points enumerated here, of which the first three refer to the very identity of Muslims and the other three to their role in society:

1- In pronouncing the shahada, Muslims testify to their faith and state a clear foundation for their identity: they are Muslim, believe in God, in His messengers, in the angels, in the revealed Books, in fate, and in the day of judgment. They believe that the teachings of Islam come from a Revelation and that they are members of the Islamic community (umma).

2- Not only is the shahada closely linked with religious rites and practice, being the first of the five pillars of Islam, but there could actually be no true rites or practice without it. An equal part of the Muslim identity is the fact of being able (and having the right) to pray, to pay the zakat, to fast, and to perform the pilgrimage. This is clearly referred to in the Qur’an in connection with “pious people who believe in what is beyond human perception and perform the prayer.”

3- More broadly, this means that Muslims should, or at least should beallowed, to respect the commandments and regulations of their religion and to act in observance of what is legitimate and illegitimate in Islam. They should not be compelled to act against their consciences, for this would be a “denial of identity.”

4- To pronounce the shahada is to act before God in respect of His creation, for al-iman (faith) is in fact a pledge (amana). Relations between human beings are based on respect, trust, and, above all, absolute faithfulness to agreements, contracts, and treaties that have been explicitly or silently entered into. The Qur’an is clear: “And be true to every promise—for, verily, [on Judgment Day] you will be called to account for every promise which you have made,” and believers are those “who are faithful to their trusts and to their pledges.

5- As believers among other human beings, Muslims must bear witnessto the meaning of the shahada before them. They must present Islam, explain the content of their faith and the teaching of Islam in general. In each type of society, and of course in a non-Muslim environment, they are witnesses, shahid, and this encompasses the idea of dawa.

6- This shahada is not only verbal. Muslims are individuals who believe and, as a result, act, constantly. “Those who believe and do good,” says the Qur’an over and over again, insisting on the fact that the shahada has inevitable consequences for the behavior of Muslims, no matter what the society in which they find themselves. To bear the shahada means to be engaged in society in every area where a need makes itself felt: unemployment, marginalization, delinquency, and so on. It also means being engaged in the process that might lead to positive reform, whether of institutions or of legal, economic, social, or political systems, with the aim of introducing more justice and real popular participation. “God commands justice,” says the Qur’an, insofar as it is the concrete manifestation of the “testimony.”

Thus, in our opinion, this concept of shahada seems to be the most appropriate way of expressing a conception that unites the identity and function of Muslims in light of the teaching of Islam. It also suits our present situation, since it allows the identity and social responsibility of Muslims to be both expressed and linked.

It is also appropriate to study its relevance in relation to the present state of the world and to the geopolitical configuration of the planet. It seems difficult, when we are experiencing a worldwide process of globalization, to continue to refer to the notion of dar, translating it in the sense of “house,” dwelling, rather than considering the whole world as our dwelling. Our world is now, whether we like it or not, an open world. Indeed, this is the intuition upon which is based the original appellation proposed by Faysal al-Mawlawi when he concludes: “In our opinion, the whole world is a dar al-dawa.”

Consequently, it seems appropriate not to translate the notion of dar in its limited sense of dwelling but to choose to give it the sense of space, which, while referring to the environment, expresses more clearly the idea of being open to the world, for Muslim populations are now dispersed across the continents. These migrations have been significant, and, despite very restrictive regulations, it appears that population movements are destined to continue: these days, millions of Muslims are settled in the West. Their fate is connected with that of the societies in which they live, and it is unthinkable to draw a line of demarcation between them and nonMuslims only on the basis of considerations of space. In our world, we hardly have to deal with the issue of relations between two distinct “houses.” It is rather a case of relations between human beings belonging to and identifying themselves with various civilizations, religions, cultures, and moralities. It is also a question of relations between citizens in constant interaction with the social, legal, economic, and political framework that forms and directs the space in which they live. This process of compounding complexity, which is a specific characteristic of globalization, mingles the factors that previously permitted us to define the various “houses.”

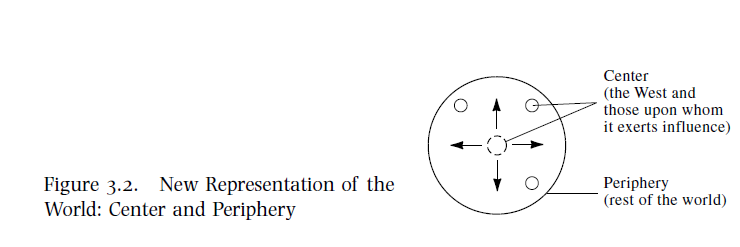

And we must go even further: the old binary geographical representation, with two juxtaposed universes that could stand face to face in relative stability, no longer bears any resemblance to the reality of hegemony and spheres of influence in civilization, culture, economics, and subsequently, of course, politics. Westernization, the legitimate daughter of multidimensional globalization, is much better expressed by the use of the notions of centre (the West and its outposts in the South) and periphery (the rest of the planet) than by a schema of two “houses” living the reality of a “confrontation” (see figures 3.1 and 3.2). The Muslims settled in the West are at the center, at the heart, in the head of the system that produces the symbolic apparatus of Westernization. In this very specific space, in the center, and in a more demanding way than at the periphery, Muslims must bear witness, must be witnesses, to what they are and to the values they hold. The whole world is indeed a land of witness, but there is a space, the fortress charged with an incomparable symbolic responsibility, which is the heart of the whole system and in which millions of Muslims now live. At the center, more than anywhere else, the principle of the shahada, which both is pivotal and extends outward, acquires its full meaning. We may schematize the evolution of this representation of the world as shown in figure 3.1. The representation in figure 3.2 brings us out of the logic of confrontation.

For Muslims at the heart of the West, there can be no question of falling back into the old binary vision (figure 3.1) and looking for enemies; it is rather a matter of finding committed partners like themselves who will make a selection from what Western culture produces in order to promote its positive contributions and resist its destructive by-products at both the human and the ecological level. More generally, it is also a matter of working for the promotion of a true religious and cultural pluralism on an international scale. Many European and American intellectuals are fighting to ensure that the right of civilizations and cultures to exist is in fact respected. Before God, and with all men, in the West Muslims must be, with them, witnesses engaged in this resistance, for justice, for all human beings of whatever race, origin, or religion.

The notion of shahada protects and safeguards the essential features of Muslim identity, in itself and in society: it recalls the permanent relation to God (al-rabbaniyya) and expresses the duty of the Muslim to live among people and to bear witness, in both action and word, to the content of the message of Islam before all humankind. And this is to happen in any society, for it is the basis of our relations with others. Western countries, called dar al-shahada or alam al-shahada (area, or world, of testimony), represent an environment in which Muslims are brought back to the fundamental teaching of Islam and invited to meditate on their role: considering themselves as shuhada ala al-nas (witnesses before humankind), according to the Qur’anic expression, should lead them to avoid all reactionary and oversensitive attitudes and to develop a self-confidence based on a deep sense of responsibility, which in Western societies should be accompanied by real and constant action for justice. This approach “from the inside” makes it possible to define the European environment as an area of responsibility for Muslims. This is the precise meaning of the area of testimony that we are proposing here and that completely upends the existing perspective. If, for years, Muslims have asked themselves the question of whether and how they were going to be accepted, a serious study and evaluation of the Western legal environment entrusts them, in the light of their Islamic terms of reference, with a mission of supreme importance. If they are truly with God, their life must bear witness to a permanent engagement and infinite self-giving in the cause of social justice, the wellbeing of humankind, ecology, and solidarity in all its manifestations. Once legitimately oversensitive and even hidden in the realms of the “abode of war” and the “abode of unbelief,” Muslims can now enter into the world of testimony, in the sense of undertaking an essential duty and a demanding responsibility—to contribute wherever they can to promoting goodness and justice in and through the human fraternity. Muslim thinking must, as we have said before, move on from “protection” alone to making an authentic “contribution,” and this model, based on the scriptural sources, should help. Muslims are, along with so many other human beings, rich in this ethic of giving. And this giving, all together, will consecrate the richness of their societies.

good

So TR draws a diagram and we are supposed to take his new definitions of life as opposed to the classical scholars’ who knew vastly more than him? No thanks.