GLOBE AND MAIL

A new phase is occurring in the evolution of Canadian Muslim youth, and it raises important questions about how they look at their society.

They are going to need more than a simple discourse on integration. They will have to move beyond the notion of a patchwork of communities living together but not connecting with each other. They will need to know that Canada’s social and political systems and culture are theirs. They will need to believe that they can embrace it fully, simultaneously retaining their own sense of self and of identity. To be able to say: « I can incorporate everything that’s not opposed to my religion into my identity, » and to assert that « anything not explicitly forbidden by Islamic principles is permissible » is an intellectual revolution.

For youth to say this means that they understand that while they respect universal immutable values, they have multiple and moving identities. Young Muslims must go beyond the « minority complex » trap – to look at themselves as being Canadian citizens and forget about being a minority. (Let’s acknowledge that it is a contradiction in terms to speak of « minority citizenship. ») To some Muslims, this is still a world of « us » and « them. » Such feelings stem from a lack of self-confidence. We in the West need a new kind of Islamic education to forge a self-confidence constructed not by seeing others as potential enemies but through a deeply understood idea of oneself.

This transformation should also apply to the majority of Canadians, who must move beyond the idea of cultural tolerance. Tolerance of minorities is a good first step – but in the long run, it will take respect and mutual knowledge for people to experience real integration into all levels of society.

There is an African proverb that says: When people start throwing stones at a tree, it means that the tree is bearing fruit. This is exactly what’s happening now. A major Islamic reform movement is under way in the West. People here have looked at Muslims and said, « We thought they were going to put aside their religion and become totally assimilated. » But young Canadian and European Muslims are replying, « We are not ready to forget who we are in order to be become who you want us to be. » Instead, they assert: « We are not the other, we are not against the other, we are ourselves and we want to be equal citizens. »

Third-generation Muslims – torn between Canadian society’s liberties and discriminations and their own parents’ traditionalist and spiritual stances – have sensed that to become genuine Canadian citizens, they seem to be expected to renounce their faith. The reality is that in the eyes of many of our fellow citizens, we are still the « other » – faithful to a foreign religion.

In this situation, one has two options: either to victimize and isolate oneself or to assert one’s otherness. What prevents us from becoming totally involved in our societies today is not legal frameworks. It is, far more, a matter of perception. Western society’s grim perception of Muslims today determines the way that people read the law and react to the presence of Muslims in their midst.

Muslim youth bears a great responsibility to change this reality. By knowing who they are, understanding where they are, and interacting with their fellow students, friends and citizens, they can change such negative perceptions.

In fact, perceptions are already changing. It’s going to be a long, slow process, but there’s no other way. Human history shows us that it takes time to change mentalities. Past immigrants have undergone the same experience: Each individual must take action at his or her local level, behaving with confidence, patience and perseverance.

But evolution will also take education, a deep faith and critical, creative thinking. These are the conditions for people to remain true to themselves and be truly free. There is no freedom without education; there is no dignity without freedom. This is what the Creator asks us to be: educated, dignified and free.

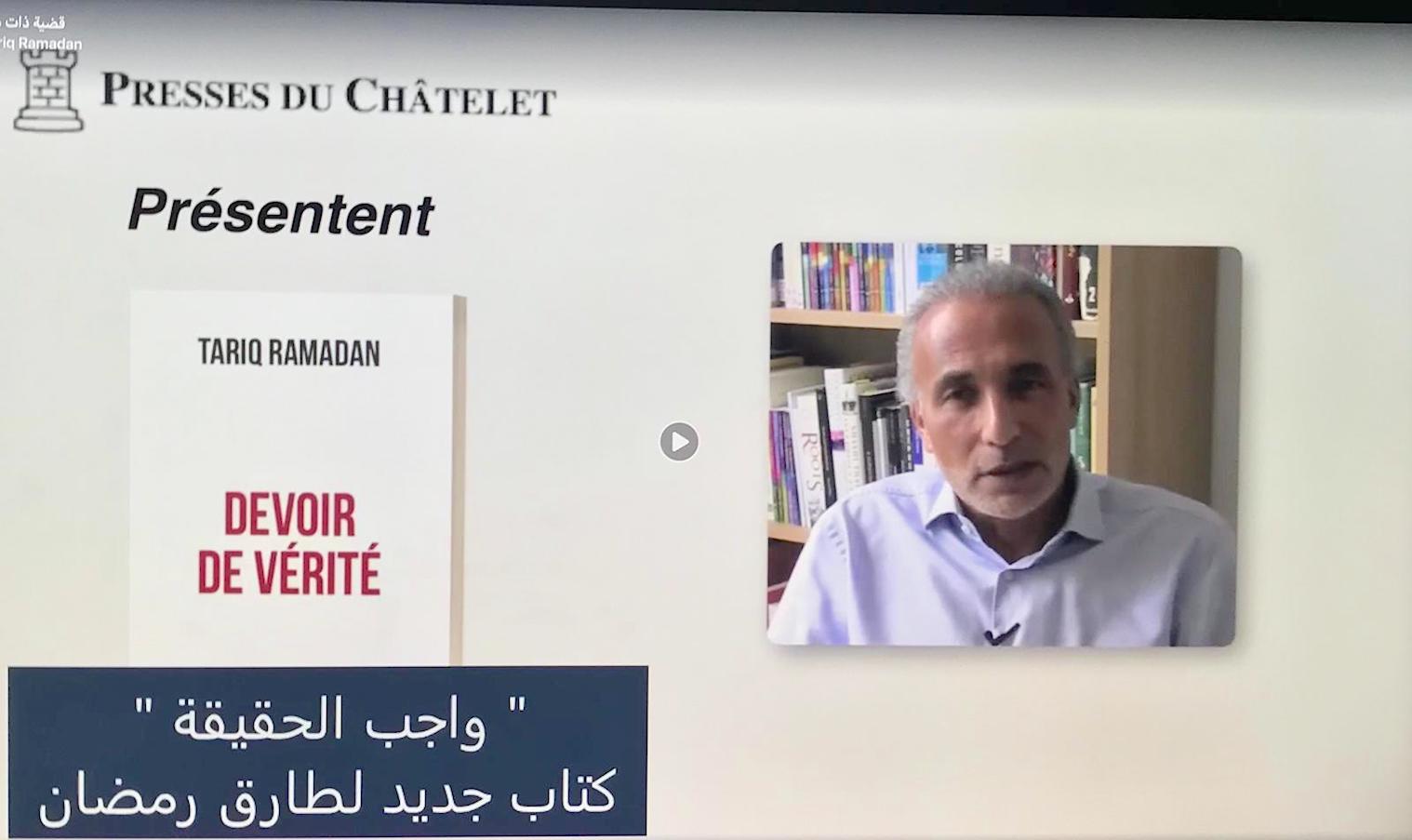

Tariq Ramadan, named twice by Time magazine as one of the 21st century’s key innovators, is a visiting professor at St. Antony’s College, Oxford, and a senior research fellow at the Lokahi Foundation. He speaks today in advance of the Institute for Research on Public Policy’s symposium on Diversity and Canada’s Future.

Source : Globe and Mail